It's the last day of November, and with Christmas looming, tiangges have been sprouting all over. Tiangges, or bazaars/flea markets are definite crowd-drawers, for the opportunity they give for some Christmas shopping that does away with hopping from one mall to another, or worse, braving the frenzied crowds in Divisoria and Tutuban.

It's the last day of November, and with Christmas looming, tiangges have been sprouting all over. Tiangges, or bazaars/flea markets are definite crowd-drawers, for the opportunity they give for some Christmas shopping that does away with hopping from one mall to another, or worse, braving the frenzied crowds in Divisoria and Tutuban.

Honestly, I'm not much of a tiangge person. It is more convenient to shop where there are dressing rooms, credit card consoles and the guarantee of a return policy. Of course products at a tiangge have lower prices precisely because of the inconvenience, but sometimes the quality is suspect, and, I'd rather go to Divisoria.

But I plunge headlong and experience the tiangge rush, gladly, twice a year, during the third week of November. It is fortunate that both the tiangge I go to are held during the same week, and during the happy time when the Christmas bonus is safely in my pockets, albeit raring to be spent.

I make exception and go to these bazaars because of several reasons. First, convenience. Second, most of the vendors in these tiangge are present every year. So I've acquired some suki, and I've developed some trust as to the quality of their products. I still smile every time I see the tie-dyed dusters I bought at one of these bazaars for barya, as they have survived about seven years of being tossed and stretched by the washing machine and still manage to be decently wearable, not having faded at all. And a friend, who marks his birthday in November, still raves about a long-sleeved polo from the tiangge which I gave him as a birthday present some five years ago.

Third, aside from the novelty items, the tiangges mostly offer products that are real necessities. Fourth, familiarity. The products on sale are the same every year, with changes only on the style front, following current trends. And fifth, most of the vendors do not have stalls elsewhere, or are located so out of the way.

So I actually look forward to these yearly events, anticipating what to buy and limiting my shopping during the rest of the year for the household items that I could buy, at steal prices,

at the tiangges.

The first tiangge I go to is a three-day annual event sponsored by the agency I work for, held at the office courtyard. The convenience is that I can just leave my office ID with the vendor without paying for, say, a pair of pants, try it on in the office comfort rooms, then go back and return it for my ID if I'm not satisfied with the fit. Or I can buy a dress or a pair of shoes for my baby girl, bring it home to fit it to her, and take it back to exchange for a more suitable size the following day.

I love this tiangge because it features mostly the companies my agency is in partnership with in the development of small and medium enterprises. So we have exporters who are subcontractors/satellite manufacturers of big name international brands. We have fresh produce from the highland plantations of Benguet, Mountain Province, Nueva Vizcaya, Tarlac and Laguna. Processed deli meats from Pampanga, baked goodies, regional delicacies and ready-to-eat dishes from all over the country. Products mostly unavailable in the malls and Greenhills or elsewhere, or are sold at higher prices.

Top photo shows Kalinga oranges, which, despite the name, come from Sagada, that breathtakingly beautiful, cool upland town in the Mountain Province. These are available year-round at the Baguio City market, but rarely in the metropolis. They are akin to the ponkan or Mandarin oranges, with their semi-flat roundness, but with the nipple-like protruberances of lemons. They are sweeter than dalandan, with thicker skin, and retaining their dual yellow-green colors when ripe. In the photo they come in the characteristic basket weave of the Cordilleras. When I was still single and without a care in the world as to the soft feel of a pillowcase on the cheek, or that babies outgrow their clothes and socks as fast as you buy them, and that I had a household with help to feed, I frowned on the office tiangge, actually laughing secretly at those enslaved by it, towing bayongs upon bayongs of purchases. But I welcomed it yearly for one reason: the food. It offered a nice diversion from the weekly office canteen fare, and afforded me a taste of authentic regional cooking.

When I was still single and without a care in the world as to the soft feel of a pillowcase on the cheek, or that babies outgrow their clothes and socks as fast as you buy them, and that I had a household with help to feed, I frowned on the office tiangge, actually laughing secretly at those enslaved by it, towing bayongs upon bayongs of purchases. But I welcomed it yearly for one reason: the food. It offered a nice diversion from the weekly office canteen fare, and afforded me a taste of authentic regional cooking. Like sinaing at ginataang tulingan sa palayok, which I first came to know through Ben-Jamon's stall at the tiangge. Also Ben-Jamon's ham, thick slices with just a hint of salt, for which I break my no-pork policy once a year.

The tiangge also acquaints me with fresh produce of other regions, like those sweet, small pineapples from Bicol. But the breakfast fare is what I eagerly anticipate - newly-cooked bibingkang galapong, light, fluffy, and buttery, sprinkled with grated fresh coconut and some brown sugar. And the sausage croissant from Baker's Fair, vienna sausages with lettuce and mayonnaise in a croissant - watching the contraption inserting the sausage filling into the croissant always makes my day. The freshly-cooked diced hopia from Baker's Fair, too. I could eat these for breakfast all the three days of the bazaar. I come in the office earlier than usual just to avoid the long lines for the bibingka.

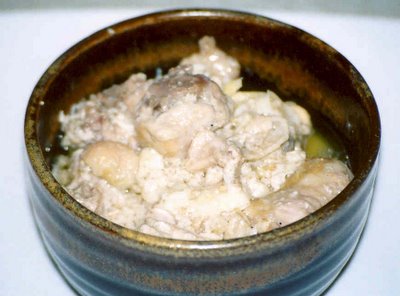

This year there was an Ilonggo bibingka, pictured here on the right, more like a mamon or the Visayan torta but lighter and fluffier, with a sprinkling of sugar. There was also some puto from Bulacan which looked like Calasiao puto, in white, brown and kutsinta varieties.

One bestseller, a mainstay of the yearly tiangge, is Mekeni Foods of Pampanga, awarded Best Meat Processing plant for several years now. Their deli meats sell lower than the leading brands, yet are comparable in taste and quality.

One new produce offered this year is a purportedly health rootcrop called yakon, which looked like a cassava or kamoteng kahoy, but can be eaten raw, developed and cultivated in Nueva Vizcaya. Raw, it tasted like sweet jicamas or singkamas, and was fun to eat. The vendor said it helps bring down blood sugar levels in the body, so it is good for diabetics. But I didn't buy any. I will have to see next year if it gained following, and wait for some verification of its health claims.

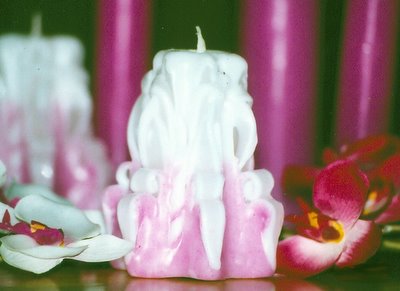

All Souls Day, re-christened Undas in the last few years or so in Metro Manila, is a time for road trips, family reunions, and the ritual gathering of relatives at the resting places of the beloved dead, for whom candles of all colors, sizes, shapes, styles and design are lighted. It used to be a noisy, merry-making event, with loud music, guitar-playing and singing, eating and drinking in the cemeteries, but now all these are prohibited, making it a quiet and orderly, albeit very tame and colorless, affair.

All Souls Day, re-christened Undas in the last few years or so in Metro Manila, is a time for road trips, family reunions, and the ritual gathering of relatives at the resting places of the beloved dead, for whom candles of all colors, sizes, shapes, styles and design are lighted. It used to be a noisy, merry-making event, with loud music, guitar-playing and singing, eating and drinking in the cemeteries, but now all these are prohibited, making it a quiet and orderly, albeit very tame and colorless, affair.  The resulting belas (rice) is a soft, almost flat and blackened deremen that smells and tastes green and smoky. It is sold by a measure of a can of condensed milk, of which about a dozen is needed to make a bigaô (bilao, a round, woven bamboo winnowing tray, pictured above) of inlubi.

The resulting belas (rice) is a soft, almost flat and blackened deremen that smells and tastes green and smoky. It is sold by a measure of a can of condensed milk, of which about a dozen is needed to make a bigaô (bilao, a round, woven bamboo winnowing tray, pictured above) of inlubi.